Early History

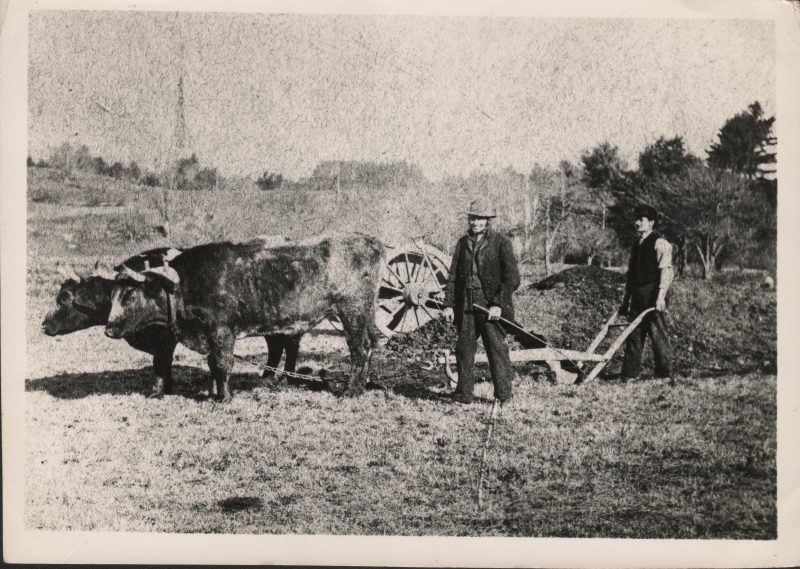

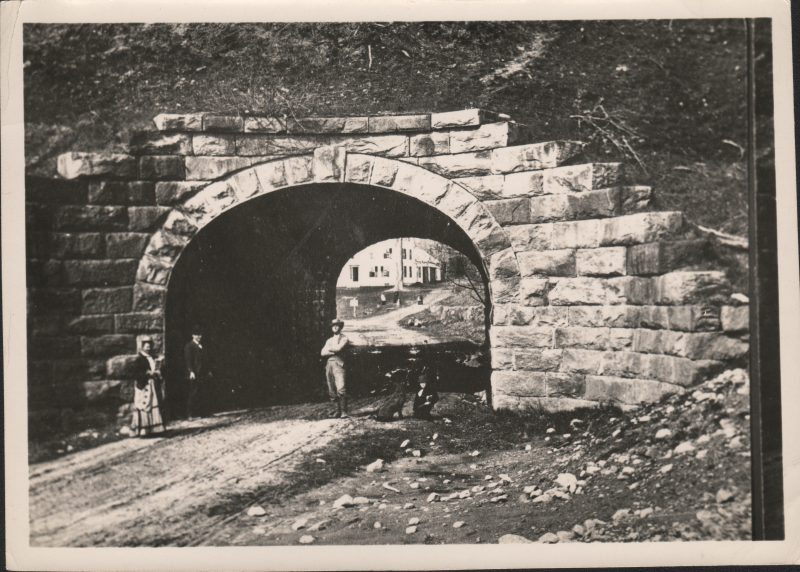

Stonewall Farm has a rich history traced through the descendants of just two families from the mid-1700s to 1989. In 1759, the acreage now referred to as Stonewall Farm, was sold by Samuel Daniels to his son John. John kept the land in the family and in 1788 sold acreage to his son Ezra, who was the first to build a house and live on the property. Ezra cleared many of the trees to create pasture for the cows and sheep he owned. Upon his death, he bequeathed the farm to his son James, who continued clearing the land for more pasture and farming areas. In fact, the entire farm known today was cleared by the Daniel lineage. It wasn’t until the death of James that the farm changed families. Upon James’ demise, in 1858, he left the farm to his daughter and her husband, Louisa and Lewis Pemberton. The Pemberton’s kept working the farm. In addition to farming, Lewis worked as a cobbler. The stagecoach route at that time came through the farm where Chesterfield Road now runs.

Louisa and Lewis sold the farm in 1908 to Carl Johnson and his wife Nanny Strongbern, both Swedish immigrants. Carl and Nanny turned the farm into a dairy. They had about 50 cows and created a milk delivery route in Keene. The farmhouse at the time was very large with 22 rooms and the Johnson’s took on boarders during the harvest months. In May 1910 a chimney fire completely destroyed the home. The family lived in the carriage shed that summer while rebuilding their new home with 16 rooms.

Norm Chase and his wife Peggy, worked with Mike Kidder, a friend, and neighbor, to ensure what we now know as Stonewall Farm, would remain an open, productive, working landscape to benefit the entire community. Mike’s passion for draft horses is what ignited the spark for Stonewall Farm’s vision. He had used Belgian draft horses in the contract logging business for 12 years and was always impressed by their power and grace. He decided to showcase their grandeur to the public by offering hay and sleigh rides. The purchase of the farm was an avenue for Mike to preserve the ways of farming for the general public. This vision led to the educational dimension of the farm with the first maple sugaring program for school children in 1991. This was followed by other school programs that now serve over 20,000 people a year.

In 1994, Mike Kidder received the non-profit status for Stonewall Farm. He saw this move as a way of giving to the community something that would remain theirs forever…..the farm itself. Now through the leadership of a board of directors, executive director, staff and community support, Stonewall Farm continues to remain a relevant and integral part of the community for generations to come.

Who Was Norman Chase?

Recollections from a Boy Next Door

by Steve Seraichick

Who was Norman Chase? Long before the founding of Stonewall Farm there was the (Norman) Chase Farm.

Today Stonewall Farm continues as a working dairy farm when all other dairy farms in the Keene area are all but a distant memory. Two important and miraculous events converged in the late 1980’s that saved the Chase Farm from the chainsaws and bulldozers of so-called modern-day progress. The first, was Norman’s long enduring, dogged, and tireless labor during his one-man farming days of some fifty years. The second, was the foresight of Michael Kidder who realized that all would be lost when Norman’s burdens would one day come to an end. Michael knew that he would eventually have to step in and help. One man along with the other and their combined determination to preserve an important link to our region’s dairy farming past, insured that this precious piece of our region’s history would never be lost.

I grew up just down the road from the Chase Farm and spent many of my childhood and teenage days “farming” and getting to know Norman. My Dad, Doctor Joseph Seraichick, had a Veterinary practice in Keene from 1942 until 1988. My father’s first office was located on Church Street in Keene, but later in 1951 he moved his entire business and our family to a new house on Chesterfield Road in Keene. When my Dad first began his practice of large and small animals there were still several working dairy farms in the Keene area. In those days my father, was the only Veterinarian in Keene proper until sometime in the early 1960’s. It would be an understatement to say, that my Dad certainly had his hands full back then. I remember he was frequently called to some of these local farms to attend to and care for sick cows and horses. It was on one of these calls that Norman requested my Dad’s help for a downed cow. I accompanied my dad often on some of these “farm” calls and joined him one late September afternoon in 1956 to see what Norman’s concern was. It was on this call that I first met Norman. It turned out that the downed cow had milk fever, a calcium deficiency.

From that day forward until my early twenties I spent hour after hour day after day on Norman’s Farm. As a little boy, farming held me spellbound. Every day was an adventure and every day I learned something new. Farming from my little boy perspective was fun and exciting. I couldn’t yet see how extremely exhausting and stressful it was for Norman. To me he always seemed to be content, and he certainly enjoyed the neighborhood kids: the Howard clan: Gary, Susan, Randy, and JoAnne, as well as the other the other children in the neighborhood: Debbie (Demers) Borden, Gary Johnson, Rebecca (Campbell) Whippee, as well as, my younger brother Peter and me. Each of us during the 50’s and 60’s lent our small hands trying our best to give Norman a little help with some of his farm chores and duties. Norman, and his first wife Teal, never had children so in many respects the neighborhood children became “Norman’s kids”!

Over time though, I began to come to grips with the true scope of Norman’s everyday work life. Growing up a stone’s throw from Norman’s farm gave me a bird’s eye view of the daily comings and goings on his farm. My bedroom window just happened to face the farm and when the weather was warm enough, I kept my bedroom window open. For about six or seven months out of the year I would wake up to Norman’s voice calling his cows in for milking at precisely 4:30 a.m. each day. He was like clockwork and never missed a beat. But 4:30 was usually just the beginning of Norman’s day. Dairy farming is not only about milking cows it is a complex difficult endeavor that most people are not aware of or understand.

When I think back now to my days on the Chase Farm, I marvel at how Norman continued farming when so many adverse forces were working against him and that despite these hurdles, he somehow managed to carry on year after year decade after decade with nary a day off. Cows need to be attended to seven days a week 365 days a year. From time to time, Norman did however, employ a “farm hand” here and there to assist him, but they could only cover a portion of his daily workload. Today I would venture that a seventy-to-eighty-hour work week was routine for Norman.

The adverse forces that Norman somehow managed to tackle each day now make my head spin. Some of these forces were totally out of Norman’s hands like the weather and milk pricing. Foremost, I suspect that weather was his biggest challenge. Each day Norman had to face whatever weather conditions came his way and in order to feed his hungry herd each day with the hay and corn (silage) grown and harvested from his land he had to wrestle with the unpredictable nature of New England weather.

Milk is considered a “commodity” in our country and the price is controlled by the Federal Government. Dairy farmers, therefore, can’t seek the highest price for the milk they produce like virtually all other products in our competitive marketplace. When a product, such as milk, cost more to produce than it can be sold for, it is easy to see why small-scale dairy farming was and continues to be for many dairy farmers a losing economic venture. I believe, Norman, beat the odds for a long time by being a “jack of all trades!” If anything on the farm needed fixing Norman usually undertook the repair work himself and by doing so saved enough pennies to stay above water. As far as I know, farming was everything for Norman, in other words, he had no choice but to somehow make it work.

There were aspects of Norman’s life that he had some control over. I think Norman was very cognizant of his own physical wellbeing and that the farm’s economic survival was directly dependent on his overall health. Any long-term injury or sickness would have doomed his farm and I’m sure he carried that thought with him as he met the challenges of each workday. As far as I know, Norman never smoked tobacco or drank alcohol. I am sure there were many days when he ached from head to toe, but as strange as this sounds, he once told me that he never took any kind of pain reliever.

Today, Norman would be considered a “steward” of his land. I think he’d get a kick out of being called that now, but from his humble perspective he was just farming the only way he knew how. Taking great care of his land provided him with a healthy herd of cows and his own economic viability. Quality hay and corn supplied the nutrients his cows needed to produce superior milk. The cows in turn furnished the fertilizer that afforded an endless cycle of sustainability. Also, I am sure the term, “organic” would render a smile on Norman’s face today. Norman always used his cow’s manure on his fields. He said once that the “new fangle” chemical fertilizers were too expensive and that “over the winter” he had a “mountain” of manure to feed all his fields.

Some forty years ago the City of Keene got lucky, an important link to our areas dairy farming past was preserved forever. Norman Chase and Michael Kidder joined forces back then to give all of us in Cheshire County and beyond a “hands on” working dairy farm for future generations of children and adults to learn from and enjoy.

Present Day

Through the summer of 2022, Stonewall Farm was home to a certified organic herd of Holsteins and Brown Swiss, the oldest and only working dairy farm in Keene, NH. Rising costs and labor challenges led to the sale of the herd, and today the farm focuses on education, sustainability, and regenerative agriculture.

At the heart of this mission is our Dorset sheep meat flock, which helps us maintain healthy pastures through intensive rotational grazing. Housed in the former dairy barn, our flock is exclusively K-Bar-K Dorsets, bred to thrive on pasture. Our meat is pasture-raised and regeneratively managed, with the first lambing season in March 2025 and products available for purchase starting in November 2025.

Set in a scenic valley, Stonewall Farm spans 120+ acres of pastures, gardens, wetlands, woods, and trails. Visitors can also explore chickens, goats, alpacas, rabbits, organic crops, an apiary, maple sugar demonstrations, a retail store, and an education and events center that draws over 20,000 people annually. Stonewall Farm remains a leader in regenerative agriculture and education for farmers, landowners, and communities across New England.